Austria to America...An Artist's Journey to Support Other Artists and Admirers. By the Incomparable Bondo Wyszpolski

Things do change in a heartbeat, don’t they? When I last interviewed Daniela Saxa-Kaneko she was serving as the interim executive director of the Palos Verdes Art Center. Not long after that the “interim” was dropped—and she was selected to head up the place, a venerable institution which has been serving the Peninsula for 90 years.

Saxa-Kaneko had plenty of ideas for what she might bring to the Art Center if the Board approved of her for the permanent position. After it became official she was on her way… for a couple of months until COVID hit really hard and everything artistic seemed to fold up and shut down overnight.

Now I’m back at the PV Art Center, almost two-and-a-half years later. Saxa-Kaneko has settled into her role as the executive director, and things are moving forward—although still cautiously. But let’s go back to the beginning.

A truly varied education

Daniela Saxa-Kaneko is originally from Austria, and her first degree of many was in hotel and travel agency management. Even during her high school years, she says, she was interested in other cultures. “I spent a summer in France to practice my French and a summer in England to practice my English.” She’d wanted to come to the States as well, which didn’t look too promising at first. But then a friend of hers met an American family who happened to be looking for an au pair. So, bingo. “That’s how I came originally. I was going to stay for half a year, and then I met my husband. The rest is history.”

Or, in this case, it’s where the history begins.

Saxa-Kaneko landed in South Pasadena. She pauses to point out two things, that she’d come from an artistic family, and that here, in the States, she wasn’t particularly interested in working in the travel industry.

Saxa-Kaneko’s husband, she says, was a physician who put his heart and soul into his practice. She helped him with billing and he, in turn, “totally supported everything I wanted to do.”

So she went back to school, in this case Pasadena City College, where she studied fashion design and business before transferring to Woodbury University. She won “Best of Show” at both schools but eventually became disenchanted by the fashion industry at large because of the way its employees were treated. In addition, she notes, “I needed something more intellectually stimulating.”

Saxa-Kaneko then enrolled at USC and earned a degree in psychology, with a minor in the study of women and men in society, “which is basically feminist studies.” It was the latter field that piqued her interest in law, and so Saxa-Kaneko went to law school.

“But always,” she points out, “the artistic part has always been there, because I need that to stay balanced. That’s essentially what my personality comes down to. I really need that balance between the intellectual part and the artistic part.”

Of man’s inhumanity to man

This is where things get a bit somber, so hold on.

“When I was in law school,” Saxa-Kaneko says, “I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do with [my] degree other than work in an area where you really make a difference, and that’s why my specialty was in children’s rights.

“When I finished law school it so happened that all the Holocaust reparations litigation was in full swing.”

One of her law school professors had connected her with the law firm Fleishman and Fisher. This was at the end of the Clinton presidency, and various matters had to be wrapped up before the change in administration. The law firm needed someone who could translate German legislation from the Nazi era, and Saxa-Kaneko was in the right place at the right time for that job. “I got to go to the reparation negotiations in Vienna when my boss couldn’t go.” She found it fascinating and became interested in mediation.

Fleishman and Fisher had an unlikely advantage: Barry Fisher played the klezmer “and had connections with the Roma community, here and in Europe, because of his musical background. That’s how the law firm ended up representing the Romani organizations in Europe.” Saxa-Kaneko went overseas with Fisher to be involved with the negotiations.

“And I have to say, it really changed my life.” She pauses, because this is a topic that affects her emotionally to this day. “You don’t realize until you actually interview these people what they went through, because what they had to rehash were things they didn’t talk to their families about.”

The Romani people, the Gypsies as they’re still called, suffered terribly under the Nazi regime, and often they’re overlooked and sidelined when the atrocities of the 1930s and 1940s are discussed. But what was important to them, and more important than the amount of any financial settlement, which may have been in the range of just $7,000, was a formal apology and the acknowledgement of what they had been forced to endure.

“They were an interesting group for me,” Saxa-Kaneko says, “because they’re always the underdog, everywhere in Europe, even nowadays.” During the war, some of them even became human medical experiments. “Things that are inconceivable,” she continues, “and you also learn in the process that it takes so little for people to turn into the worst animals.”

I point out that unspeakable acts are at this very moment playing out in Ukraine and, furthermore, with my own recent reading about the pre-Christian kingdoms of the Near and Middle East, one encounters that familiar cycle of conquest and relentless murder.

“You see the parallels,” Saxa-Kaneko replies, “and you think, Okay, how can this happen again? But it happens all over the place, over and over again. I don’t think that anybody really learns from history, which is sad. But it’s true.”

We have digressed somewhat, and yet, Saxa-Kaneko says, “In many ways it really formed who I am today. It made me much more sensitive to a lot of things.” She also realized that she’d rather be a mediator than a litigator: Better to try and resolve misunderstandings through mediation than to drag things out—psychologically, financially, etc—through litigation. In short, this realization led to Saxa-Kaneko returning to the classroom where, at Pepperdine, she earned her Masters of Law and Letters. She worked primarily as a full-time mediator after this, eventually becoming the director of the Disability Mediation Center, one of the four programs of the Disability Rights Legal Center, an independent non-profit organization located at that time on the campus of the Loyola Law School but not otherwise affiliated with it.

Over the next few years, this was the course that Saxa-Kaneko’s life followed, and apparently it was a line of work she both enjoyed and was very good at. She notes, however, that “it’s very tiring when you listen all day long to people’s problems.” After her husband died, 15 years ago, she took a job as executive director of the Loew Vision Rehabilitation Institute (named after its founders whose name was Loew), a clinic that specialized in assisting people who were losing their eyesight. She was with the company for five years, having helped them build the company from the start. At the same time, now widowed, Saxa-Kaneko signed up for a ceramic class in Laguna Beach “because I just wanted to do something new and fresh.”

Up the ladder, one rung at a time

Knowing little about the Palos Verdes Art Center, Saxa-Kaneko one day came by to find out more about it and then decided to take a ceramics course. Within a short time she’d become associated with the Artists’ Studio, helping out in the shop, and when an opening came along for a membership coordinator she took the job.

Generally speaking, and in layman’s terms, she liked the vibe of the place and decided to stick around.

“And so,” Saxa-Kaneko says, “when Joe Baker left I thought it was a perfect opportunity for me to apply for the executive director position, because I had already been an executive director and I kind of knew what it entails.” And because she’s been involved in both the membership and human resources departments she’d already secured a foothold in the organization. She wasn’t someone from the outside who didn’t know the people or the community, which had bedeviled the previous executive director. Saxa-Kaneko, by contrast, knew the people, lived locally, and was taking classes as well. “So for me it was like the perfect fit, and I guess the Board thought so too.”

Then the wind went out of the sails in March of 2020, two months into her new position.

“Little did I know when I started in January that COVID was coming along and was making everything much more complicated than I’d anticipated.” All of Saxa-Kaneko’s plans, from expanding membership to adding classes and exhibitions, came to a standstill. Well, a near standstill. There were a few online events, classes, etc, but that’s hardly the same.

Despite the worst of the worst, the PV Art Center was able to hold onto its employees. It also secured a PPP loan the first year, and it was fully forgiven the second year. However, celebrations planned for the 90th anniversary could not take place, although Saxa-Kaneko would like to have a belated party marking the milestone once enough people feel comfortable in returning. And, actually, they have been making their way back for the opening of recent exhibitions. Although, as I write, COVID rates have been rising, which could presage a new surge and prolonged mask and vaccine mandates.

Getting everyone involved

“I really believe that art is a very important aspect of anybody’s development,” Saxa-Kaneko says, “especially for children, because it helps them with so many things, especially cognitive development and problem solving. And I think it also helps with self-confidence.” She notes that she enjoys looking in on the classes for the younger children and seeing what they’re doing creatively, in what could be a small window before they become too self-conscious to pursue what’s remarkably original. “When you look at the smaller kids, they’re sometimes better than the older kids because they’re not inhibited. That’s amazing to me.”

Saxa-Kaneko then emphasizes that adults need this in their lives as well, “a little play to kind of just let go of the everyday stress.” And this leads us to a discussion of what she’s tried to accomplish these past couple of years.

This includes building a broader curriculum that goes back to the teaching of basic skills. “I really think that foundation has to be there.” Fundamental building blocks should be in place, and then it’s a matter of “letting people be who they are” so they can evolve their own style. “I don’t believe in a teacher coming in and taking over their painting, for example.”

What ties in with this is PVAC’s special mornings program in which each Friday special-needs students are bussed in from across the L.A. Unified School District. Each class, Saxa-Kaneko says, is small, 10 to 15 children, so that each one can receive the personal attention he or she deserves. “It’s really remarkable what creativity they bring to the table that you would never have imagined,” she says. “The special needs population is very, very dear to my heart, and I would like to expand that.”

Currently, she adds, there aren’t many grants available for this, and therefore the program is funded in general by corporate and private sponsorships. Ensuring that this continues is, again, one of Saxa-Kaneko’s primary goals. She’d also like to get younger folks more involved, after-school classes for the five to 12-year-old set, not to mention enticing classes for high school-aged students.

There’s also a need for Saturday and evening classes. “We haven’t really offered too many night classes for people that are working,” Saxa-Kaneko says, “and I think there is a need for that out there. So that’s what I see, and bringing in more workshops with artists from the outside so you can have more exposure to other things.” This could even involve artistic disciplines beyond or in conjunction with the visual arts. Poetry, literature, theater, film—why not?

As far as exhibitions are concerned, for it’s these that bring in the larger public, “We kind of want to challenge people. It may not always be too popular, but sometimes they need that little nudge to develop further and see new things,” which is, she emphasizes, “the only way you can kind of open up and broaden perspectives.” That said, Saxa-Kaneko is quick to acknowledge, “I accept that people don’t like certain things; that’s part of it. Art appreciation is very subjective.

“But, in any case, we’re a community organization, and my other goal is really to rebuild community and to expand, to reach out to other segments in the community—younger ones, different ethnic groups—so I think there’s a lot to be done and we would like to reflect that in every aspect. We need to expand inclusiveness in what we do,” and to see it mirrored in the Board and the teaching staff. In terms of exhibitions,” Saxa-Kaneko continues, “I’m thinking too that we have to do something that will focus on some of these communities. It’s a challenge and it’s not necessarily going to happen overnight, but we’re working on it.

“So that’s in a nutshell where I think we ought to be going.”

Photography credit: Arturo Garcia-Ayala

Background, GIFTED: Collecting the Art of California at Gardena High School, 1919-1956, an exhibition on view at PVAC through Nov. 12, 2022

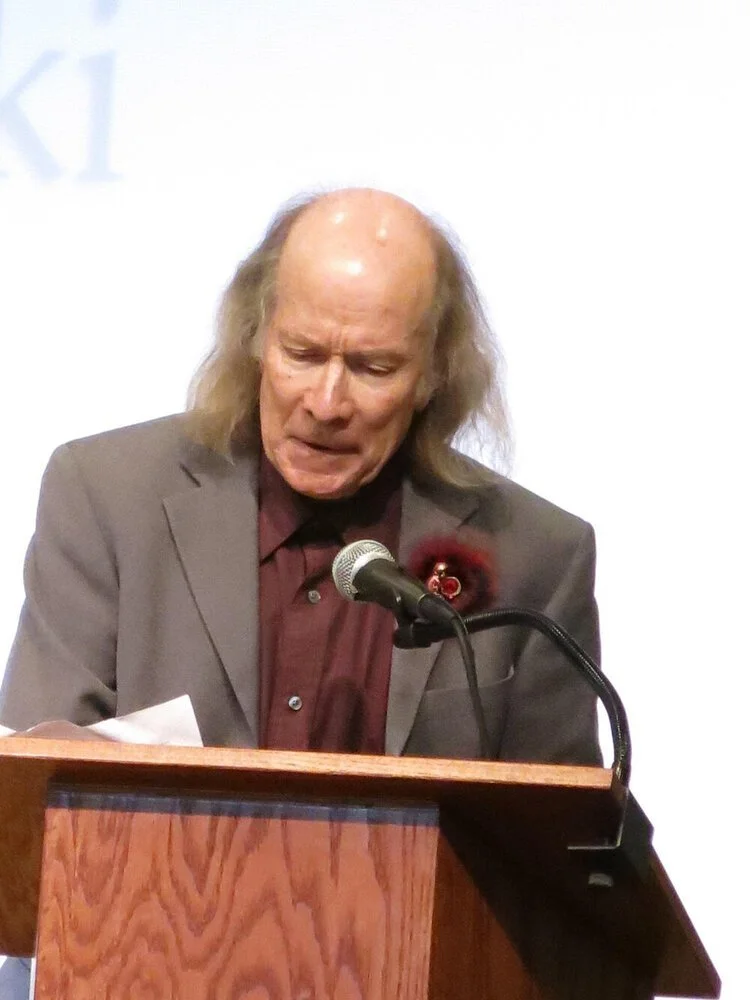

Many of you have seen Bondo Wyszpolski with notepad and camera in hand at all kinds of community events, ready for interviews and photo shoots. Bondo has also reviewed thousands of plays, movies, concerts, books, art shows and operas. He prefers the Baroque operas by Henry Purcell and Handel, while his favorites among modern composers are Sergei Rachmaninoff and Ralph Vaughn Williams, and he also enjoys some African music. He favors the Symbolist painters of the 1890s and though he studied the standard authors from Poe to Hemingway in college, he now reads mostly foreign writers such as Portuguese novelist Jose Saramago and Gabriel Garcia Marquez from Colombia, both Nobel Prize winners. In fact, it was after The Los Angeles Times published one of Bondo’s book reviews that Kevin Cody, the owner and publisher of the Easy Reader, hired Bondo full time as an arts and entertainment editor in 1993. Before that Bondo wrote for the now-defunct Beach Cities Newspapers. Bondo grew up in Palos Verdes Estates, attended Lunada Bay Elementary School, Margate Middle School, and Palos Verdes High School.