Fun and Fancy Free–Roscoe Arbuckle’s Comedy Shorts In Long Beach By Historian Lea Stans

OutWest 1918

The smiling face of Roscoe Arbuckle, once a starring comedian at Mack Sennett’s legendary Keystone studio and then a star in his own right, isn’t as familiar as it used to be. All too often he’s associated with the infamous 1921 Labor Day scandal, when actress Virginia Rappe fell ill at a party he hosted and died several days later. While a jury eventually acquitted Arbuckle of causing her death, it’s overshadowed much of his legacy. Which is a shame, for when we study the history of silent comedy there are few slapstick two-reelers as lively, gleeful, and entertaining as the ones Arbuckle made in his own studio from 1917-1919. And some of the cream of that crop was filmed in Long Beach, when Arbuckle moved his studio from the confines of the dense city to the freedom of the sunny, wide-open spaces of southern California

While Arbuckle’s own talent alone was enough to create guaranteed “laughmakers,” he did have a secret weapon at the time: Buster Keaton, who in 1917 was 21 years old and fresh off the vaudeville stage. Keaton had been getting ready to appear in the elaborate theater production The Passing Show of 1917 when he was invited to visit Arbuckle’s studio, Comique (pronounced “Cuh-mee-key”). Located in a four-story building on East 48th Street, the Comique studio was gearing up for Arbuckle’s first release The Butcher Boy (1917) when Keaton dropped by. Arbuckle invited him to do a scene revolving around a bucket of molasses (and its resulting mess). Fascinated by the moviemaking process, Keaton quickly decided to join the Arbuckle team.

Trio plus Luke the dog

The Butcher Boy was followed by The Rough House, His Wedding Night, Oh! Doctor and Coney Island (all 1917), chock full of choreographed mayhem that’s been described as “slapstick ballet.” In one film a delivery boy and a cook might reduce a household to chaos as they fight over a maid’s affections; in another there might be an all-out war between all the characters with bags of flour whizzing and exploding all over a general store. Keaton would be well matched in these scenes by the uninhibited Al St. John, Arbuckle’s nephew and fellow Sennett veteran, who was also a great pratfaller. In a sense Arbuckle, Keaton and St. John were an informal comedy trio, well before the likes of the Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers.

It wasn’t long before the New York studios (Comique soon left East 48th Street for the old Biograph studio in the Bronx) were proving to be a bit cramped. For instance, the shooting of His Wedding Night took place during the hottest parts of summer and the cast could only bear to work for 30 minutes at a time. Arbuckle decided a change was needed, and that change would be a move to southern California, which was swiftly becoming the main hub of early filmmaking. Specifically, he would move Comique to the Balboa Amusement Producing Company in Long Beach.

The Balboa complex at 6th Street and Alamitos Avenue was built in 1913 by Herbert M. Horkheimer and his brother Elwood. It was only a mile from the beach–the fresh air was no doubt a welcome change from crowded New York. It featured a number of buildings painted green with white trim and manicured grounds, giving it a campus-like feel. It also boasted all the latest motion picture equipment and the largest glassed-in stage at the time. Several studios churned out films at Balboa, from Paramount to Mutual, but Roscoe Arbuckle was far and away the biggest star the Horkheimers had–no doubt his arrival caused considerable excitement.

A Country Hero 1917

The first Comique short filmed in sunny, breezy Long Beach was A Country Hero (1917), which is unfortunately lost today, although surviving stills and descriptions give a good sense of what it was like. Arbuckle constructed a fictional town called Jazzville on Balboa’s grounds. It also featured Joe Keaton, Buster’s father and former vaudeville partner, in a prominent role. A highlight of the film involved an automobile being hit by a train–it took two takes and two separate cars to get the shot just right.

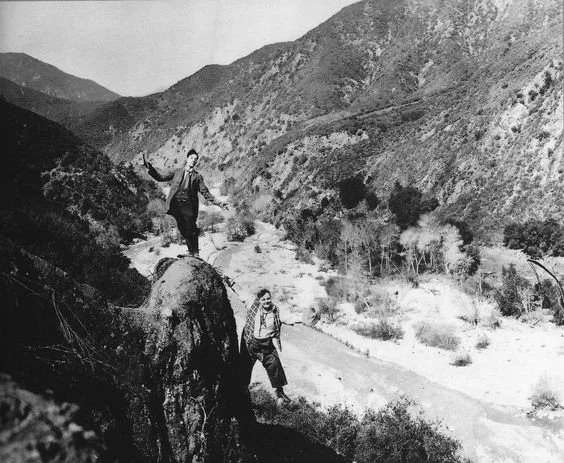

OutWest 1918

Inspired by the freedom of the new location, their next short Out West (1918) would be even more ambitious. This time telling a more cohesive story set in the wild West, it began with an impressive sequence where Arbuckle gets chased on top of a moving train before ending up in a rough town of Mad Dog Gulch. The train sequence was filmed in the Mojave desert, while Mad Dog Gulch would be built in the San Gabriel Canyon near Los Angeles. The next short The Bell Boy (1918) would scale back a bit by revamping the Jazzville set from A Country Hero and setting much of the action indoors in a quirky village hotel. But Moonshine (1918), a fourth wall-breaking satire about bootlegging, would again film in San Gabriel Canyon. Interestingly, the cast would be stranded at their location for ten days when spring rains caused a nearby river to flood. Filming on location in those days wasn’t always for the faint of heart.

Moonshine

Moonshine was followed by the gleeful dark comedy Good Night, Nurse! (1918), where Arbuckle ends up in a sanitarium run by doctor Keaton. This time location shooting was done at the Arrowhead Hot Springs resort, where the cast was apparently allowed to run as amok as they liked. The next comedy, the freewheeling The Cook (1918), would mark the end of this brief but very bright era. In the summer of 1918 Buster was drafted to fight overseas in World War I and was granted a two-week delay in order to finish the new film. Set mostly in a restaurant before abruptly switching to an amusement park, The Cook shows signs of being hastily done but also has a delightful bubbly energy–especially in a scene where Arbuckle and Keaton get carried away by music and start imitating a dancer’s floor show.

Good Night Nurse

While Keaton would eventually return to Comique after serving in France, the studio’s time at Long Beach had drawn to a close. WWI had hurt the Horkheimers’ business and they had to declare bankruptcy. Arbuckle’s studio would eventually end up in Edendale on Allesandro Street. But the days in Long Beach, with all their promise and sunny real-world locations, were no doubt a big influence on Keaton and his solo film career in the 1920s. He would speak of what was, to him, the true magic of cinema: “If you wanted cities, deserts, the Atlantic Ocean, Persia, or the Rocky Mountains for your scenery and background, you merely took your camera to them…Nothing you could stand on, feel, or see was beyond the range of the camera.”

Note: The book Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life by James Curtis was an important source for this article–and this writer couldn’t recommend it more highly!

Lea Stans is a historian from Minnesota who runs the blog Silent-ology, covering

the people, films, and culture of the silent film era. She has contributed to Silent Film Quarterly, The Keaton Chronicle, and Comique: The Classic Comedy Magazine. She is also a regular columnist for Classic Movie Hub and contributed a chapter to CHASE! A Tribute To The Keystone Cops. She can be reached at: LMStans5@gmail.com