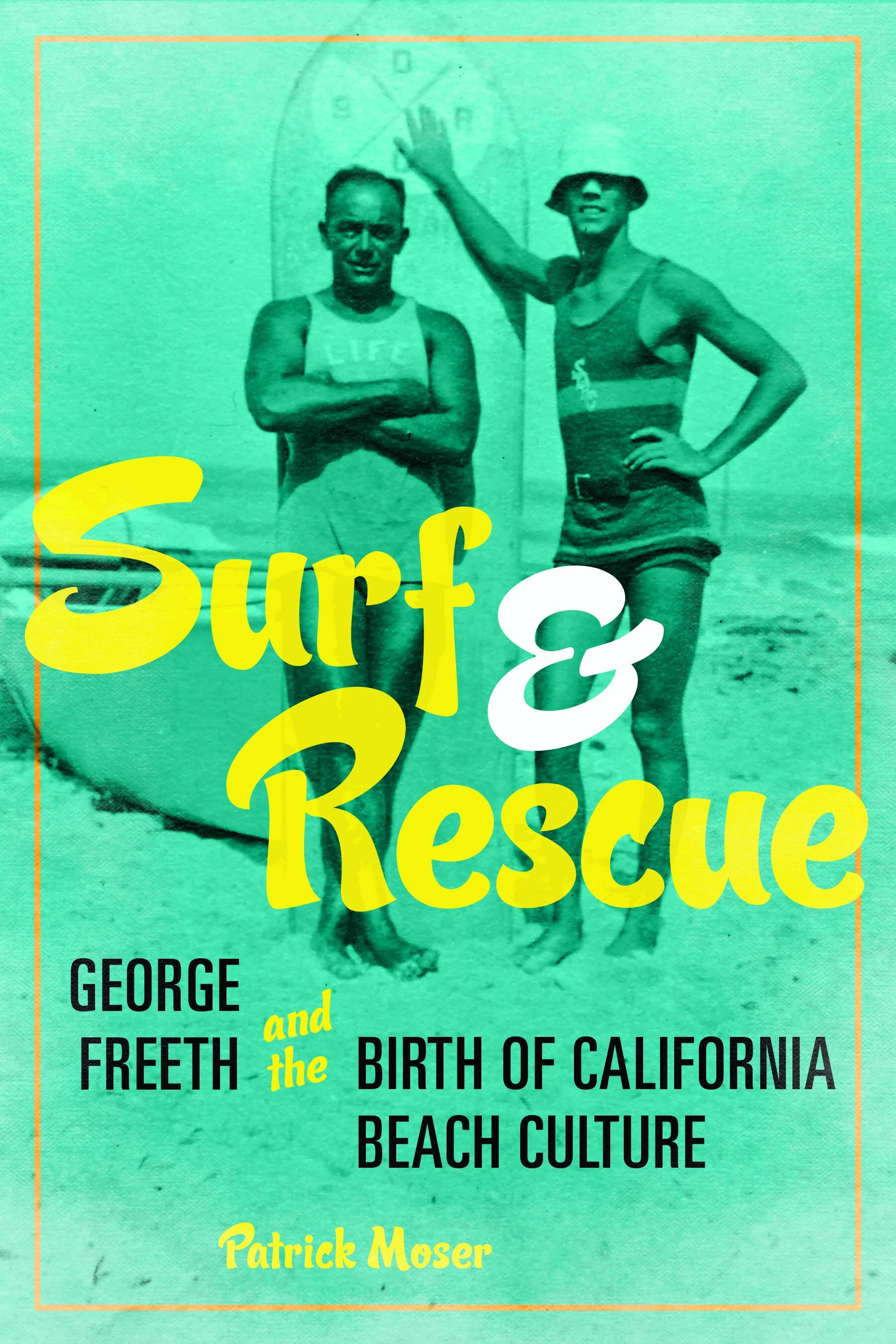

Redondo Beach and the Birth of California Beach Culture By Author Patrick Moser

George Freeth, the mixed-race Hawaiian who popularized surfing in California when he arrived in Los Angeles in 1907, bounced around quite a bit in his life. As a child he lived on Laysan and Clipperton islands, following his father who managed guano mining operations. He lived in San Francisco as a teenager, competing in swim races at Sutro Baths. In his twenties and thirties, of course, he taught surfing, swimming, and lifeguarding from Los Angeles to San Diego before dying in this latter city during the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. Of all the places he lived and worked, however, Redondo Beach held him the longest—more than six years out of the eleven that he lived in the Golden State. What was so special about Redondo?

I landed there myself when I was eighteen years old, in 1981. I had just moved into a condemned motel on the corner of First Street and PCH in Manhattan Beach, fresh from Northern California with the odd goal of becoming an auto mechanic. I started taking classes at Santa Monica College, but I wanted to surf so I’d found the motel room for a hundred bucks a month and spent my free time riding waves. When my money ran out, I took a job as a busboy at New Tony’s restaurant on the Redondo pier, where the Maison Riz building now stands.

I used to pass the bronzed bust of Freeth riding my bike to work. I didn’t know who he was, or what he had done. He had surfed in that area right behind his bust. In his day, it was called Wharf Number One. He started giving surf exhibitions there in late December 1907—no wetsuit, of course—entertaining locals and visitors for Henry Huntington’s Redondo Improvement Company, which owned the bathhouse (where Freeth worked as a lifeguard and swimming coach), all three wharves, and the whole waterfront. Huntington had essentially founded Redondo in 1905, and he (or someone in his organization) hired Freeth away from Abbot Kinney in Venice so that the Hawaiian would attract visitors to Huntington’s budding resort town. In my day, that surf spot was called the Horseshoe—a cul-de-sac of water surrounded on three sides by the pier. New Tony’s had large glass windows along the south side of the restaurant, with fabulous view of Palos Verdes. We tracked swells as they rolled in during the night. Once the restaurant closed at midnight, I’d search out my buddy Mike Conway, a busboy at Castagnola’s restaurant, which sat at the center of the pier overlooking the Horseshoe, and we’d leap off the pier railing into the water, surfboards in hand.

The Horseshoe tested your nerve and reflexes. The waves pushed through the wooden pylons, jacked straight up, then broke furiously for about five seconds before the whole thing exploded on shore. The bigger the swell, the faster the drops. One night Mike took off on the first wave of a set, and I stroked into the second. Halfway down the face, I saw his head bobbing right in the line of my bottom turn—he had wiped out. I had half a second to decide if I wanted to get barreled or guillotine my friend.

Hmmph.

I jumped.

I was riding a Dewey Weber twin fin. I can tell you exactly how far apart those fins were because I have a scar on my left nostril, and another under my left armpit. I took the wave right on the head, and those fins slashed me like an angry mugger. I crawled onto the sand with a broken nose, completely dazed, right there behind the bust of George Freeth.

Here’s Freeth describing his first wipeouts in California to a reporter from the Honolulu Advertiser in September 1910: “I wouldn’t more than rise to the surface when another one would land on me hard, and I had to double up tight to avoid being pounded to pieces, but after a while I got used to their ways and could ride them without any trouble.”

If only I’d known more about Freeth and followed his advice, I might have avoided bussing tables the following week with a Bozo-the-clown nose. But I don’t mind the scars so much these days when I think about where I got them, at a place that is really ground zero for the origins of California beach culture.

Freeth is important because he insisted that his lifeguards learn how to surf. This skill not only kept them in top shape, but it also taught them to understand waves and currents so that they could be more effective life savers. Surfing’s growth in the early years was a by-product of this training, spreading from the lifeguards to local enthusiasts and general beach visitors. For the next four decades in California, as surfing steadily grew from a novelty to a lifestyle, the best surfers in the state were always lifeguards. If we count Duke Kahanamoku as an honorary member of that group—he in fact saved numerous lives while living in California—they include Charlie Wright and Tom Blake in the 1920s, and Pete Peterson throughout the 1930s; after World War II a younger crew innovated both activities into the 1960s—Tommy Zahn, Joe Quigg, Matt Kivlin, Phil Edwards, Greg Noll, Buzzy Trent, Mike Doyle, to name a few.

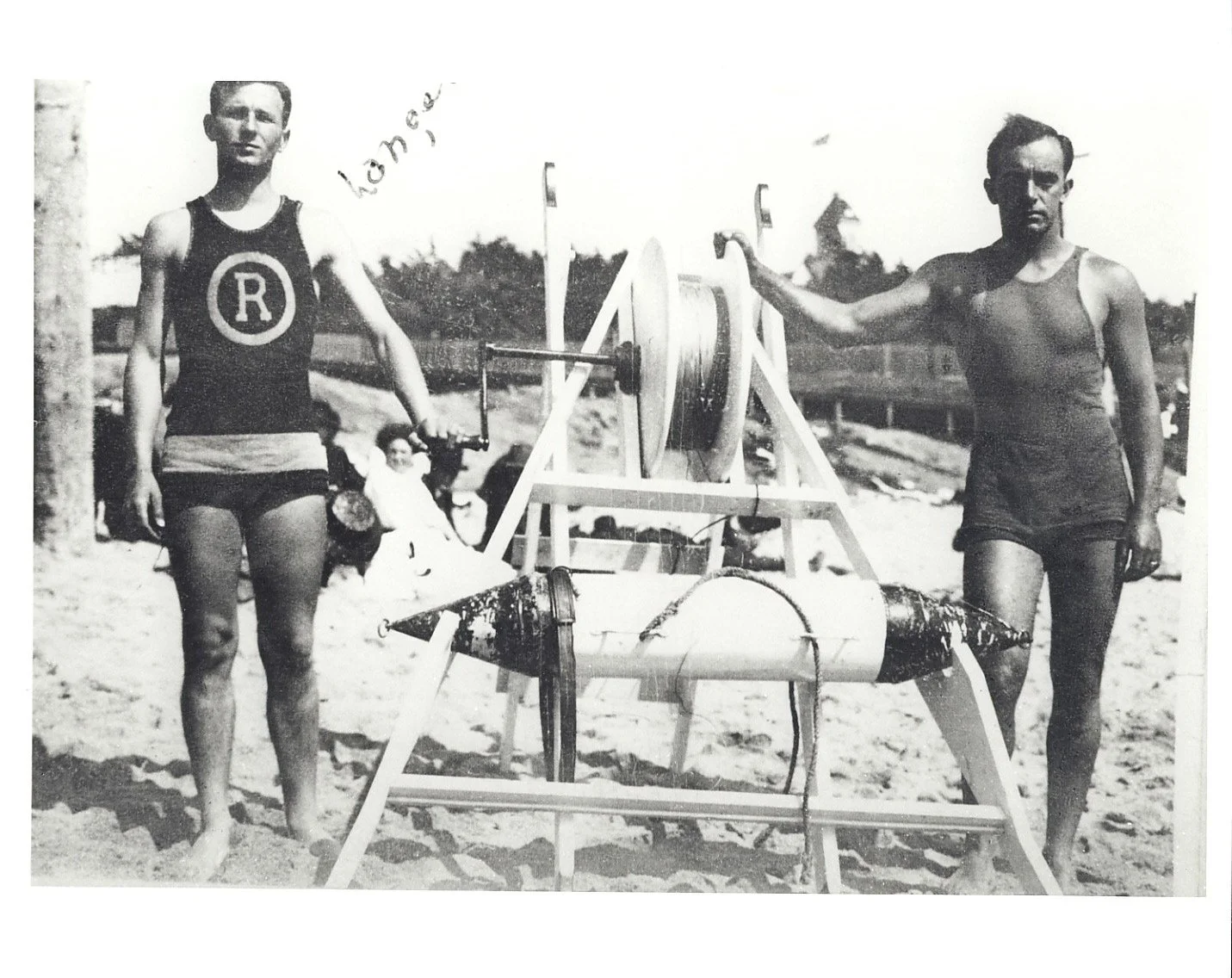

The combination of surfing and lifeguarding formed the twin pillars of California beach culture as we know it today. Because Freeth conducted the majority of his surfing and lifeguarding in Redondo Beach—including such technical innovations as a beach tripod connected to a reel and buoy system, and a three-wheeled motorcycle to extend the range and speed of his rescues—we can say that Henry Huntington’s resort town served as the fertile soil (or sand, in this case) that gave birth to California beach culture. Even when Freeth’s reputation as a swim coach grew, and the Los Angeles Athletic Club hired him in October 1913 to develop the top swimming club in the nation, he continued to live in Redondo Beach, choosing to commute into downtown Los Angeles on Huntington’s electric trolleys rather than give up his life by the beach.

Why was Redondo so special?

Redondo would have had a lot of appeal for Freeth. The small town had more of an industrial hum than Venice, with its three wharves off-loading tons of lumber, oil, and other freight destined for the booming development of the Los Angeles basin. A deep-water canyon, beginning less than five hundred feet from shore and dropping down more than thirteen hundred feet, allowed bigger ships to approach the wharves, thus giving Redondo a natural advantage over Venice in its development as a commercial hub for the region. Freeth had spent much time around ships and harbors in his youth. One can imagine him feeling right at home in Redondo, a port that cleared four hundred vessels in 1906, the year before he arrived.

Venice had a similar population as Redondo—about three thousand people—but it was founded as a resort town; its constant preoccupation was entertaining visitors. And though Redondo was moving in a similar direction, the trains running out to all three wharves—their cars loaded directly with freight from the steam and sailing ships—gave the town more of a workmanlike atmosphere that may have attracted Freeth.

It’s worth mentioning that the same deep-water canyon that brought in bigger ships also creates bigger waves in Redondo: that gap in the ocean floor allows swells to push closer to land before rising up and breaking with greater force. From a surfer’s perspective, Redondo would have been a better choice for Freeth’s exhibitions, especially in winter when the waves are bigger. Redondo was also well known for its great hauls of fish—bass, mackerel, barracuda, yellowtail, trout, sardines, halibut and sand dabs—likely another benefit of the canyon’s presence. Freeth introduced spear fishing with a glass mask at Redondo in the summer of 1912. He would reportedly swim around the base of the wharves and spear twelve to fourteen fish at a time.

Overall, we might posit that Redondo became a special place for Freeth because, in addition to his lifeguard work in the bathhouse and along the beaches, he was able to enjoy great waves and then—in true Hawaiian style—go fetch his dinner in the surf.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I wanted to learn more about the life and accomplishments of George Freeth. The book began as a novel based on Freeth’s life. I gave up after a hundred pages or so because I was clinging too closely to the few facts that I knew about him—that’s where the writing kept taking me. So I decided that I had to write his biography before I could write a novel about him. Once I started digging into his life, I realized that I had more than a biography: I had a history of California beach culture yet to be told. I rely heavily on databases of newspapers from Freeth’s era. The thousands of articles have helped me fill in the gaps in Freeth’s life and represent a great boon for doing the same for the history of a sport like surfing.

George Freeth sporting a period bathing suit that highlights one of his major contributions to the development of beach culture in early twentieth-century California: teaching swimming at bathhouses from Los Angeles to San Diego. Courtesy Los Angeles County Lifeguard Trust Fund, Witt Family Collection.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

I’ve long admired William Finnegan’s writing, especially his surfing material, much of which appears in Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life. His ability to evoke the characters, places, and experience of surfing is the gold standard for the sport, one I aspire to. I admire books like Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild. It’s well researched yet accessible. It tells a compelling story, with careful attention to language and narrative structure. He knows how to keep a reader turning the page. I like the idea of presenting a history that is both authoritative and interesting to read. My book is an attempt to make the academic research that I do accessible and meaningful to a broad audience. To do that I draw on techniques that creative writers use to tell their stories: character development, detail and description, figurative language, and plot structure.

Freeth’s instruction of surfing to children taught them to understand ocean waves and currents, a foundation of knowledge crucial to the development of California beach culture. At Redondo Beach, circa 1910. Courtesy Los Angeles County Lifeguard Trust Fund, Witt Family Collection.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I realized that Freeth’s instruction of surfing and lifeguarding in early twentieth-century California established the foundation of the state’s world-famous beach culture. As I tracked his influence in both activities, I discovered that their combination—essentially his insistence that the lifeguards he trained learn how to surf—set the stage for a culture that developed around riding waves and enjoying the many opportunities that beaches provided.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

Freeth’s story offers a corrective to persistent beliefs that Caucasians who had arrived in Hawai`i in 1907—principally Alexander Hume Ford and Jack London—“saved” surfing from extinction in the early twentieth century through their promotional efforts. Although the two mainlanders were enthusiastic boosters of the sport, Freeth represented the cultural continuity of Native Hawaiians practicing this centuries-old tradition even as he adapted it to his life and work in California.

Ludy Langer and Freeth manning Freeth’s torpedo tube and wire-reel innovation, Redondo Beach circa 1913. Courtesy Los Angeles County Lifeguard Trust Fund, Witt Family Collection.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

I hope readers see how one individual can make such a positive impact on people’s lives. Freeth did this not only by saving many lives himself as a lifeguard, but by transforming the way people thought about the beach. At a time when many beach visitors were afraid of the ocean because of the persistent problem of drowning, Freeth showed them that the ocean could be a tremendous source of pleasure. In the nearly dozen years he spent in California, he gave thousands of lessons in swimming, surfing, diving, and ocean rescue. He taught a generation of Southern Californians that they too could have fun and confidence in the ocean.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I’m reading Jack Kerouac’s On the Road right now. It’s the Original Scroll edition, which I didn’t think I’d like because it’s about three hundred pages without paragraph or page breaks—just one huge block of prose. But the energy of the writing has carried me along. I don’t even notice the lack of breaks anymore. It’s raw and passionate. The writer in me admires Kerouac’s ability to grab his readers, put them in the car seat beside him, and just bomb through the story. I’m enjoying the ride.

Patrick Moser

Drury University

pmoser@drury.edu