Whale of a Day is On it's Way: Taking a Break from the Norm - The Gray Whales Return to the California Coastline By Photographer and Contributor Steve Tabor

Mariners and coastal residents along the Pacific coastline have witnessed the annual gray whales migration from the Bering and Chukchi Seas southward towards the warm lagoons of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula for hundreds of years. It was the regularity of this over 10,000 miles round trip journey that nearly brought gray whales to the brink of extinction.

In the 1800’s, it was not long before the whaling industry discovered that the gray whale adult and juvenile left their arctic water feeding grounds in early fall, to mate and give birth to their calves in the warm waters of the lagoons in Baja California. Captains of the whaling ships set their course to rendezvous with the whales in the shallow waters of the Baja lagoons. The shallow warm waters were an excellent habitat in which to give birth and perform their mating behaviors but, it allowed them to become easy prey for the whalers’ deadly harpoons. The journals kept by the sailors on the whaling ships provide a tearful description of how the light blue waters were transformed into a crimson red as the tally of harpooned whales grew.

Eventually, the demand for whale oil diminished as petroleum products were refined into kerosene and lubricants which in turn led to the downturn of the whaling industry. Realizing the whaling industry’s deep impact on the whale population led to a moratorium on the senseless killing of these majestic mammals. Over time, the gray whale population grew and reestablished itself, and continues to fascinate whale watchers along the west coast of North America.

Unlike members of the toothed whale family such as sperm whales, pilot whales, dolphins and porpoises, gray whales are baleen whales. Instead of teeth, they have a series of baleen plates composed of keratinous material, (similar to human fingernails) that grow from the bottom of the upper jawbone. Most baleen whales such as humpback whales, blue whales and fin whales, feed by scooping in large quantities of sea water containing small crustaceans such as krill and small fish. Before swallowing their catch, they use their tongues to expel the water out through the slits between the baleen plates which traps their prey inside of their mouths. Once the sea water is expelled, the prey is swallowed.

Gray whales use their baleen in a similar way, but instead of scooping their prey from the open ocean, they scrape the sediment on the ocean bottom for ghost shrimp and crab and other arthropods living in silty ocean bottom. Gray whales use their baleen to expel the water and silt using their tongues and trap the tiny creatures in their mouths. As they expel the mix of ocean water and silt, they leave a muddy trail floating on the ocean’s surface.

Researchers have long studied the social patterns, feeding patterns, and other behaviors of many toothed and baleen whales all of whom are members of the Cetacea family. Many whales have their skin scarred or have parts of their tail flukes or pectoral fins bitten off by predators As for any baleen whales, including gray whales, not only do they experience the scarring and predator attacks, but as they age, barnacles attached to various parts of their body. Over time some are rubbed off or fall leaving a markings and differences in the skin color. Researchers use these scars, disfigurements and coloration patterns to identify individuals and monitor their lives as they navigate their aquatic habitat.

As for gray whales, researchers have been able to identify and closely monitor them as they travel along the migration path from the arctic waters to the in the lagoons of Baja. By identifying pregnant females, researchers have been able to identify their calves and follow them throughout their life cycle.

It is through their research and monitoring of the migrating gray whales that have led researchers to some fascinating discoveries in recent decades that are causing them to re-think what was previously believed about these gentle giants.

Researchers have confirmed after giving birth in the lagoons of the Baja, the new mothers remain in these waters producing amazing quantities milk rich in fat to feed to their new born calves in order for them to gain size and strength before beginning their long journey north to their home in the arctic waters. It is estimated that the calves can gain as much as one hundred pounds per day as they suckle.

Researchers also observed during the migration period, adult whales lose significant amounts of weight. Not only is found in nursing females, but researchers have come to belief that the weight loss occurs because adult males and females do not eat until they returned to their summer feeding grounds in the arctic waters.

However, beginning in the 1990’s the Cascadia Research Collective (CRC) in the state of Washington began to notice some interesting changes in some gray whales during their northern migration. Members of the CRC started noticing gray whales in the North Puget Sound in particular around the southern ends of Whidbey Island and Camano Island. Other areas included the Saratoga Passage, Port Susan, Gedney Hat Island, and the Snohomish Delta. Eventually, the gray whales in these areas became known as “Sounders.”

As part of their study, researchers examined satellite photos of the area which revealed large feeding pits in the swallow waters. As the sightings continued into the 2000’s, the CDC was able to identify seven male and three female gray whales through skin samples they have gathered.

So far, the CDC has not documented any calf sightings, but they are attempting to discover possible answers to this phenomenon. Among the current hypotheses are that calves tend to migrate during a later time period than the time researchers spot the Sounders. Another thought is female gray whales are intentionally keeping their calves away from the shallow waters in the Sound in order to avoid them becoming prey to orcas, also known as killer whales, or other predators.

As part of their observations, researchers have noted, and are attempting to find answers to, is the first spotting of gray whales occurred in the early 1990’s and the second wave of sightings occurred in the timeframe between 1999 and 2000. During both of those time periods, there was a high mortality rate among gray whales, nearly 33% of the gray whale population.

Since the 2000’s the sightings have occurred with such consistency that the CDC researchers have devised a method for approaching the gray whales and attaching tracking devices equipped with suction cups that are mounted to their backs which provide video and data transmissions. These transmissions provide an amazing amount of information about a variety of behaviors including feeding. From these devices they have been able to confirm through the analysis of the whales’ fecal samples that they are feeding and digesting ghost shrimp that are found in the Sound’s coastal waters.

A little further down the coastline researchers along Oregon’s central coast in the area of Depoe Bay have made significant findings as well. These waters now support a resident population and a part-time population of gray whales known as the Pacific Coast Feeding Groups.

During a period between June and late October, a group of approximately two hundred resident gray whales appear along the Oregon coast. Some of the population is known to remain in the area a brief amount of time, while others tend to stay a significant amount of time. In late October, the gray whales leave to join other gray whales on their southern migration.

During their time off the central Oregon coast, researchers have been able to verify that these whales consistently return and continue to demonstrate their regular behavior patterns including feeding. Through photographs, researchers have been to identify sixty of the whales of which forty of them have been found consistently wandering the coastal waters of Oregon between Lincoln City and Newport.

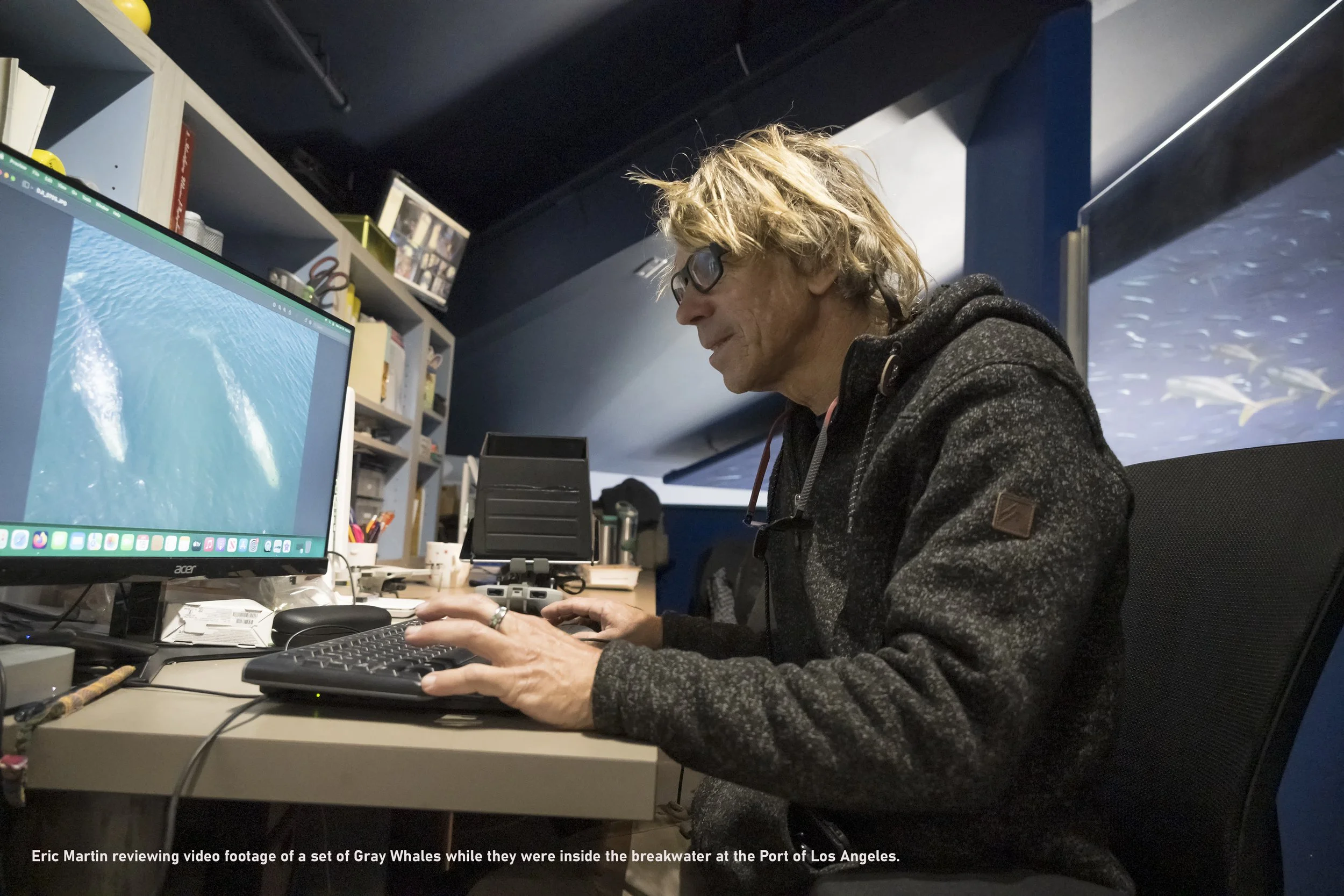

In the waters between Long Beach and the Palos Verdes Peninsula, we beginning to experience an unusual change in the behavior of passing gray whales. For several years, Eric Martin, Head Aquarist and Facilities Director for the Roundhouse Aquarium in Manhattan Beach, has been researching and documenting dolphin pods inhabiting the waters in Santa Monica Bay and the migrating gray whale population. Approximately eight years ago, during the period of the northern gray whale migration, he received word from a whale watching boat stating that they were starting to see gray whales inside the breakwater at the Port of Los Angeles. Since that time, Martin has launched his small boat near Cabrillo Beach and attempted to photograph and identify the gray whales entering inside the breakwater of the Port of Los Angeles.

Martin was not able to capture a few photographs, but he was really able to fully comprehend the reasons why they were entering one of the busiest harbors in the United States until he acquired and began using a drone. Using his drone, Martin is able to observe the whales from above which provides a more comprehensive view of the whales and their behaviors.

In 2021, Martin received a phone call from his son, who happened to be working on a whale watching cruise that day in the harbor. His son reported that they had been observing a juvenile gray whale in the harbor who was engaging in feeding behaviors, but they could not verify their sighting. Martin attempted to launch his drone and capture the whale and its behavior, but he was unsuccessful.

Following that report, Martin received reports from other local sources that the gray whales were spotted inside the Port’s breakwater. While using his drone during multiple visits to the harbor, Martin was able to capture videos of adult gray whales in the shallow waters inside the breakwater. The drone view allows Martin to observe the silty mud trail on the surface of the water just above the whale’s mouth. Through his numerous observations of this behavior, Martin believes that the whales are actually engaging in their feeding behaviors. Additionally, the gray whales Martin has documented show no signs of severe weight loss nor did they show signs of stress. In fact, they appear to have intentionally entered and have little intention of leaving the area.

From his research, Martin has discovered that gray whales appear inside the breakwater in about mid-February and remain within the confines of the breakwater for several weeks. Not only do they appear to be feeding, but they also rub their forty-ton bodies along the ocean bottom in a similar way to what has been observed in other environments. Martin estimates that the population is between five and eight whales. However, he has not been able to identify the whales or confirm if they have previously visited this area. Also, he has been able to verify the appearance of two juvenile whales have appeared in the area inside of the breakwater.

Although Martin has been able to confirm that ghost shrimp and other favorite arthropods are found in the sediment samples taken at the breakwater, observed the muddy trail on the surface of the water indicating feeding behaviors, and he is seen feeding pits in his videos, he has yet to confirm that the gray whales are actually ingesting these items.

Martin states that his findings have created more questions than answers, but his drone will assist in providing more answers as he continues to document these behaviors. Martin is confident that he has accumulated sufficient video footage to compare this year’s whale sightings, that will hopefully occur, to last year’s sightings. He is devising a method to secure a fecal sample to clearly determine if these whales are ingesting food sources in our harbor.

With his research and the research being conducted by others, Martin is hoping that we will find answers to such questions as: Why there is a decline in the gray whale populations in their arctic feeding grounds and along the migration path? Are these changes in migration behavior part of climate change? Is coastal development contributing to this behavior and population changes? Are these changes in migration behaviors actually signs of previous migration and feeding patterns?

Even if such answers are found, it is most certainly that these creatures will continue to provide a sense of wonder and fascination.

Steve Tabor Bio

This South Bay native’s photographic journey began after receiving his first 35 mm film camera upon earning his Bachelor of Arts degree. Steve began with photographing coastal landscapes and marine life. As a classroom teacher he used photography to share the world and his experiences with his students. Steve has expanded his photographic talents to include portraits and group photography, special event photography as well as live performance and athletics. Steve serves as a volunteer ranger for the Catalina Island Conservancy and uses this opportunity to document the flora and fauna of the island’s interior as well as photograph special events and activities.

Watch for Steve Tabor Images on the worldwide web.