"Lost Art" brings Oz 'Home' to Southern California By Brady Schwind

"Lost Art" brings Oz 'Home' to Southern California

By Brady Schwind

Brady Schwind, the founder of "The Lost Art of Oz" project with John R. Neill's original artwork for the half-title page to L. Frank Baum's THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ (1913).

For over a century, The Wizard of Oz has been America’s best loved fairy tale, and from almost the very beginning, Los Angeles has played an indelible part in the story’s enduring legacy. Oz’s Chicago based author, L. Frank Baum, found Southern California’s beaches irresistible, and yearly winter pilgrimages to the coast fueled his imagination - and inspiration - for stories that delight children of all ages to this day.

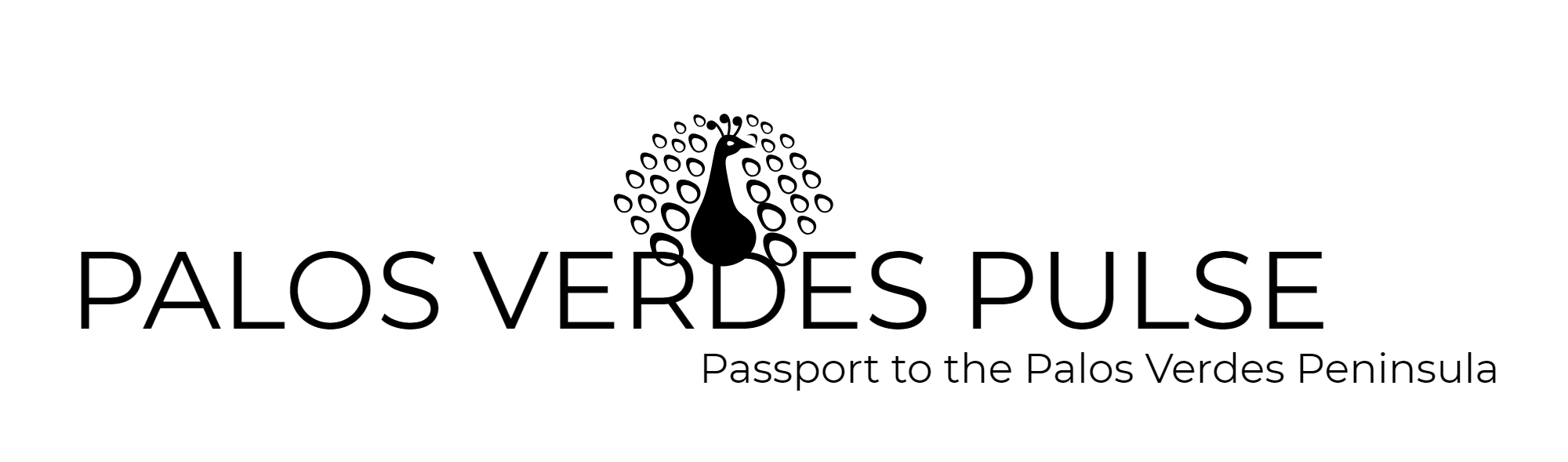

Left - Assorted original pen and ink drawings (with strong pencil underlay) by W.W. Denslow for L Frank Baum's first and most well known Oz book, THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ (1900). These drawings were offered at auction in 1913, when Denslow failed to make payments on his storage unit, and eventually found their way to the permanent collection at New York Public Library.

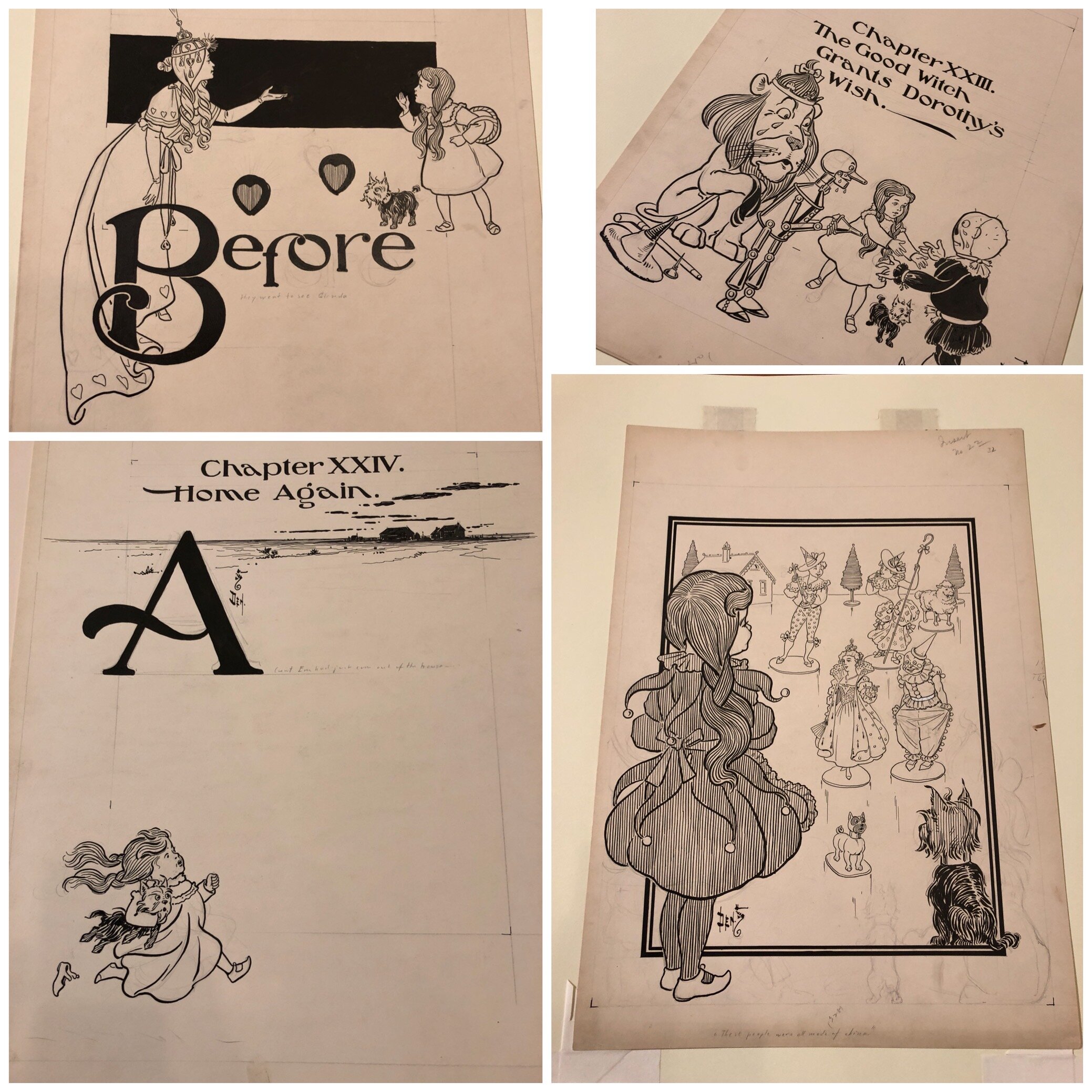

Right - John R. Neill's original pen and ink drawing for the half-title page to L. Frank Baum's THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ (1913) alongside an example of how the drawing was reproduced in the first edition copies of the book. Color was added to the artwork in the printing process.

My love affair with Dorothy and her fantastical journey down the yellow brick road began, like it does for so many, as a young child watching the classic MGM film. Shot in Culver City on soundstages filled with Technicolor visions (and a pitch perfect performance by Judy Garland), the movie remains as timeless and wondrous as it was in 1939. When I hit grade school, I excitedly discovered that before the movie, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a book. And that the book had a LOT of sequels!

Discovering that my great-grandmother had antique copies of the Oz books from her childhood turned me into an instant collector. Along with Baum’s whimsical writing, I especially adored pouring over the books’ fantastic drawings. The series’ illustrators, led chiefly by W.W. Denslow and John R. Neill had the gift of making Oz seem at once like a place beyond my wildest dreams: but so real in its depictions, I wouldn’t be surprised to see one of its wonderful creatures standing on a local doorstep.

Left - Brady Schwind gives a lecture on the history of Oz artwork at the El Segundo Museum of Art (ESMoA) for their exhibition: "Experience 41: Oz"

Right - Brady Schwind and scholar, Bill Campbell survey damage to an original pen and ink illustration discovered in the vaults of Columbia University in New York. Drawn by John R. Neill for L. Frank Baum's second Oz Book: THE MARVELOUS LAND OF OZ (1904)

When I was presented with the opportunity to acquire a few original drawings used to create the illustrations for the Oz books for my collection, it was a dream come true. What I didn’t realize was how rare the artwork actually was. For the Oz series (written between 1900-1960) nearly 4,000 original drawings were penned to illustrate the books. The work was done mostly ‘for hire’ for the books’ Chicago publisher, Reilly & Lee, but by the time the company did an inventory of their archive in 1983, there were only a few dozen pieces left.

Left - "I'm the Cook" -- one of the few surviving watercolor drawings John R. Neill created for the Oz book series, this example depicts the characters of "Dorothy" and "The Wizard" in the Land of the Fuddles in L. Frank Baum's THE EMERALD CITY OF OZ (1910) alongside an example of how the drawing was reproduced in the first edition copies of the book. The watercolor was discovered thirty years after being loaned for a window display in the basement of Marshall Field department store in Chicago.

Right - John R. Neill's original Pen and ink drawing of "Dorothy," Glinda," and "Ozma" for the frontispiece to L. Frank Baum's final book, GLINDA OF OZ (1920) alongside an example of how the drawing was reproduced in the first edition copies of the book. Color was added to the artwork in the printing process.

What could have happened to it? Where could all this magnificent and creative art so vital to my childhood have gone? I simply had to find out, and in the fall of 2018, the “Lost Art of Oz” project was launched.

The scavenger hunt to find and catalogue the surviving original artwork has since taken me around the world to visit libraries, universities, antiquarian book dealers, and private collectors, everywhere from Dallas to New York to Minneapolis to London. One particular challenge has been that the artists didn’t sign much of their work; if you are only familiar with the world of Oz and its characters as they appear in the 1939 film, you might not recognize the first depictions of the story.

The search has also been one of identification and preservation. Often, when found, the illustration boards are damaged or incorrectly labeled. Pieces have turned up not only at the Library of Congress but at swap meets and on eBay, so the hunt has required a wide net of exploration. It was a common practice in the early 1900s to send the original artwork out to be used for promotion and window displays. It wasn’t always returned, and this has led to artwork being discovered in some quite unexpected places. A handful of the series' beautiful watercolor paintings turned up - thirty years after they were loaned for a book display - in the basement of Marshall Fields!

Of course, as irony would have it, the greatest spoils I’ve found by far have been in California - the land so close to Baum’s own heart. Once I began to dig, like a hidden trunk unlocked, treasures unfurled. A film scholar in San Pedro had a drawing she had purchased at a Wizard of Oz convention as a child. A book dealer south of LAX showcased a drawing he'd bought at auction and had lovingly restored. And a chance phone call from a coastal gentleman revealed a trove of extraordinary drawings that hadn’t been seen in decades.

Where the artifacts have ended up over the past century has been as varied and unpredictable as the people who ended up with them -- but what all these collectors seem to share is a deep affection and attachment to what this fairy tale means, both at the personal level and to our American culture.

Like Dorothy on her journey, the quest has also led me to an extraordinary band of allies: scholars, experts and friends eager to share and be a part of the continued discovery. Perhaps most meaningful of all are those who don’t own art but who call simply to share Oz books they loved from their own childhood, or valuable copies excitedly rediscovered in an attic from their own family’s past.

As if to signal the timelessness and universal appeal of the story, last summer, the El Segundo Museum of Art (ESMoA) launched the wildly popular “Experience 31: Oz.” The exhibit lovingly brought together what might be the largest amount of Oz artwork ever assembled in a traditional museum setting.

As it turns out, the loss of all that artwork reflects art history. The art of Oz was lost because at the time it was created, it wasn’t valued. Of course, few could have anticipated that one hundred years later, a simple children’s book would have become such an ineffable part of our heritage.

Examples of the original Oz books -- the most beloved and best-selling American children’s series of the 20th century.

Brady Schwind surrounded by his collection of rare Oz books and artwork at his home in Palos Verdes Peninsula.

Finding and sharing the artwork, especially with those who’ve never had the chance to see the illustrators’ works in person, is my continual joy -- and like all great adventure stories, the quest goes forward. With each new drawing I rediscover, I’m reminded of the message that lies at the center of The Wizard of Oz itself: in our search, heart, brains and courage will always lead us on the path back ‘home.’

Do you have vintage books, artwork, or memorabilia related to The Wizard of Oz? If so, The Lost Art of Oz project would love to hear from you. Visit them on the web at www.lostartofoz.com and follow them on Facebook and Instagram.

Brady Schwind is an award winning writer, director and performer who has called Palos Verdes home for nearly two decades. While his life long journey as a storyteller has seen him traverse stages from Hollywood to New York, Brady’s passion for one particular enduring children’s classic has recently taken him on a story book adventure of a different kind. In his search to uncover “The Lost Art of Oz”, Brady finds himself returning ‘home’ and to the story’s local California roots.