Shining the Light on Peninsula History Pt. Fermin Lighthouse Celebrates 150 Years of Standing Watch By Photographer and Contributor Steve Tabor

Built on the cliffside overlooking the entrance to the Los Angeles Harbor and the Santa Catalina Channel, the Pt. Fermin Lighthouse (Lighthouse) lit its lamp in late 1874, and stands as a lasting monument to City of Los Angeles’ and California’s rich history.

The Lighthouse’s history actually dates back to the 1792 voyage of British explorer, George Vancouver. Prior to stopping in Southern California, Vancouver met with Father Fermin Francisco de Lasuen at the San Carlos of Monterey Mission while visiting Alta California’s Monterey Peninsula. Fr. Lasuen was Fr. Junipero Serra’s successor as President of the California missions.

Although, Fr. Lasuen grew tired of the struggle between navigating the ambitions and influences of the Spanish government while remaining loyal to his service as Jesuit friar, Vancouver was impressed with Fr. Lasuen. Vancouver states, “Our reception at the mission could not fail to convince us of the joy and satisfaction we communicated to the worthy and reverend fathers, who in return made the hospitable offers of every refreshment their homely abode afforded. This personage was about seventy-two years of age, whose gentle manners, united to a most venerable and placid countenance, indicated that tranquilized state of mind, that fitted him in a eminent degree for presiding over so benevolent an institution.”

Vancouver arrived in San Pedro Bay later in the year, and named Pt. Fermin and Pt. Lasuen in honor of the friar.

As the westward expansion and the discovery of gold in California brought thousands of people via land and sea to the soon to be Golden State, hundreds of ships made San Pedro Harbor their port of call. By 1855, the ever increasing maritime traffic created a demand for a safe entry route in the harbor and the need to establish a guiding light to assist with navigating the coastline. Despite the need, it was not until 1872 that a site was selected, and Congress allocated $20,000 to build a lighthouse with a fog signal.

Pt. Fermin Lighthouse along with several other lighthouses were built in the same time period and were designed by the U.S. Lighthouse Board’s Chief Draftsman, Paul J. Pelz. As Chief Draftsman, Pelz designed lighthouses located on the east and west coasts of the U.S. as well as the Gulf of Mexico.

Paul J. Pelz designed lighthouses located on the east and west coasts of the U.S. as well as the Gulf of Mexico. Also, in 1888 he became the lead architect on the much delayed Library of Congress construction project.

Photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress

His iconic brownstone tower lighthouses were designed by Pelz between 1871 and 1876 and rise above the landscapes at St. Augustine (FL), Bodie Island (NC), Sand Island (AL), Currituck Beach (NC), and Morris Island (SC).

The St. Augustine Lighthouse is one of Pelz’s classic brownstone designs. The Keeper’s living quarters were separated from the lighthouse structure.

His Victorian style lighthouses include Pt. Fermin Light (CA), Mare Island Light (CA), East Brother Light (CA), Hereford Inlet Light (NJ), Pt. Adams Light (WA), and Pt. Hueneme Light (CA). These lights were designed between 1873 to 1875. Unfortunately, Mare Island Light, Pt. Hueneme Light, and Pt. Adams Light were demolished and only Pt. Hueneme Light was replaced by a concrete art deco style building.

The tall circular stairways leads to the lantern room high atop the St. Augustine Lighthouse.

Although brownstone lighthouses and the cottage lighthouses look very similar in their design, it is the height of their light towers that can greatly vary. In addition to the candlepower of the light, which is determined by the Fresnel lens placed over the light, the height of the light tower also determines how far the light beam will travel. The Pt. Fermin Lighthouse has a five story light tower. Other similar designs have a two story light tower.

Although the site for the Lighthouse had been determined, the land was not publicly held. In fact, in anticipation of an expanding Port of Los Angeles and the need to establish a lighthouse along the coastline, Phinneas Banning began purchasing a number of properties along the coast line in hopes that the federal government would realize the need for a deep water port to serve the expanding City of Angels.

Looking towards the southeast from the lantern room reveals the Port of Los Angeles breakwater, Angels Gate Lighthouse and the entrance to the Port of Los Angeles.

While Banning made overtures to Congress, 78 separate lawsuits were filed regarding the acquisition of the land and the necessary permits to erect such a compound. According to some unsupported accounts, former City of Los Angeles Mayor and wealthy landowner, Jose Diego Sepulveda became so frustrated with the process and unresolved lawsuits, that he sold the necessary parcels of land to the City of Angeles for $35.

With the land dispute resolved, builders looked to California’s natural supply of Redwood and Douglas fir as the primary building materials. The Lighthouse’s multi-prism lens framed with brass fittings was hand built at inventor Augustin Fresnel’s factory in France at a cost of nearly $12,000.

At the time of its construction, Pt. Fermin Lighthouse was the only structure near the Point. Eventually much of the City of San Pedro and the land surrounding Pt. Fermin would be developed by George H. Peck.

Construction was completed late in 1874 and on December 15, 1874, the oil lamp was lit inside the fourth-order Fresnel lens producing a 2,100-candlepower beam of light that was visible for 13 miles.

At the time, the location of the Lighthouse was extremely remote, the hillsides surrounding the property were vacant and the newly expanded harbor was still under development. The location was so remote that the only sounds that seemed to interrupt this tranquil environment were the squawking of the gulls, the sounding of the foghorn and the occasional thump of a disoriented bird attracted to the signal beam striking the outside glass surrounding the lantern room.

Mary and Ella Smith, sisters, were appointed as the first lightkeepers at Pt. Fermin. Previously, they served as lighthouse keepers on a spit land, Ediz Hook, near the City of Port Angeles on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. The sisters remained at the Lighthouse for nearly eight years.

This is a model of the original Fresnel lens installed in the Pt. Fermin Lighthouse. Over its years of service, the lens was upgraded to improve the performance of the light beam.

In 1881, Mary and Ella’s sister, Abbie, who lived in the Washington Territory, died of a stomach ulcer. In January 1882, Ella resigned her assistant keeper position and returned to the Washington Territory to marry Abbie’s former husband, Samuel Stork.

Keepers were required to provide their own furnishings. None of the furnishing currently on display at the Lighthouse were original furnishings, but they are appropriate for the time period the Lighthouse was in operation.

Following Ella’s departure, the U.S. Lighthouse Board appointed Civil War disable veteran, James Herald, as the Assistant Keeper. Herald arrived at Pt. Fermin with his wife, Matilda and their two daughters with his eyes on assuming the role of head keeper and its $200 per month salary increase.

The spacious primary bedroom was located in the rear of the house to provide a quieter sleeping environment.

Shortly after arriving Herald and his wife began to intimidate Mary and impugn her character. Even the Lighthouse’s hired hand, Nathanial Parsons, were targeted by Herald and his wife. In response to these episodes, Mary wrote several letters to the 12th District Inspector, Cmdr. George Coffin, describing the couples actions, but Coffin took no action to remove Herald from his position.

In place of wooden slats across the bed frame or a box spring, a rope was strung across the bed frame to serve as a foundation for the mattress. The wooden key on the quilt would be used to assist with tightening the rope to increase the firmness of the bed, thus giving rise to the phrase, “Sleep tight.”

As time continued, Herald accused Mary of selling U.S. Government coal intended for use at the Lighthouse for $20 dollars to a City of Wilmington merchant. In another correspondence to Cmdr. Coffin, Mary disclosed she had engaged in a transaction, but it was with the intent to obtain a softer coal that would burn better in the Lighthouse’s kitchen stove. She pointed out in her defense that another incident a commander instructed her to exchange coal for firewood. She further went on to deny any other of Herald’s accusations.

Eventually, Cmdr. Coffin reached the point where he felt that must address the situation between Mary and Herald. No matter his personal beliefs, he knew the decision needed to be approved by the U.S. Lighthouse Board. Cmdr. Coffin acknowledged that Mary did sell the coal without permission and after she retired the U.S. Government horse assigned to the Lighthouse, she used the feed intended for the horse to feed her personal horse.

The secondary bedroom was smaller than the primary bedroom, but had a coal burning firebox for heating. A small room adjacent to the secondary bedroom could be converted into a third bedroom, if necessary.

As for Herald, Cmdr. Coffin stated, “as he is not physically competent to the outdoor duties of the station. He and his wife each have bad tempers and he being a cripple has no control over her. I am inclined to think her the first cause of ill feeling(s) between the keepers and the final cause of this difficulty.”

Cmdr. Coffin concluded that Mary should be removed for her position as keeper or reduced to an assistant keeper. However, by having Mary remain at the Lighthouse, Cmdr. Coffin thought that the same situation may recur since the Board would only appoint a male as a keeper or assistant keeper.

Prior to the installation of indoor plumbing water closets were located in the living quarters.

As for Herald, Cmdr. Coffin recommended that Herald be removed from this position. Cmdr. Coffin knew that the Board would favor of any cost reduction opportunities, and knew the Board would appreciate his recommendation of removing Mary and Herald from the Lighthouse and recommending a married couple replace the two positions would be appreciated by the Board.

There is no information as to how Mary spent her time following her departure from Pt. Fermin, but many feel the disciplinary action taken against her was harsher than actions taken against other individuals accused of similar violations.

Early in its operation, three freshwater cisterns stored rainwater that would be used for daily fresh water needs. The primary cistern could store up to 10,000 gallons of water.

Initially, the Lighthouse’s signature beam was a flashing white and red beam at 20 second intervals. The flashing effect was accomplished by having the lens rotate 360 degrees by placing it on the flat surface of a geared wheel, similar to a Lazy Susan on a dining table. The geared wheel was turned using a chain and weight gravity system similar to the system used on a cuckoo clock. The weight on one end of the chain would be lifted to a position just below the geared wheel. As the weight attached to the chain fell to the ground, the wheel would rotate of the lens in a 360 degree circle.

To achieve the change in the light signal from white to red, two red glass panels the height of the glass lens were installed on the geared wheel in front of the lens and directly across from one another. As the geared wheel turned the lens, every 90 degrees the light would change from white to red as the light passed through the prism and red pane of glass in front of the lens before the light was sent out to sea.

No matter where you live, the kitchen is the heart of the home. The slab of soapstone was placed below the stove to insulate the kitchen floor from the heat of the wood burning stove.

In 1889 the light was changed to a fixed white beam. In 1912, the fixed white beam proved too difficult to distinguish from other lighthouses in the area, and the solid white beam was changed to a flashing white beam. The pulsing pattern of the beam would be noted on Light Lists and allow captains to identify each specific lighthouse they were passing by.

Following the Smith sisters, Captain George N. Shaw served at Pt. Fermin for 22 years. During his time, the population around the Lighthouse grew as real estate developer, George H. Peck, acquired and developed much of the land in San Pedro. As the population grew, the Lighthouse became a popular attraction. With permission of his superiors, Shaw opened the lighthouse to visitors and conducted tours.

Irby H. Engels followed Shaw in 1904. Engel’s was replaced by William L. Austin in 1917. Austin and his wife, Martha, were previously assigned to remote and rustic lighthouses at Pt. Arena in Mendocino County and Pt. Conception in Santa Barbara County. Prior to arriving at Pt. Fermin, the Austin family grew to include seven children, and another would be born while they lived at Pt. Fermin. The couple was excited to come to Pt. Fermin not only because it featured many conveniences including indoor plumbing, which was originally gravity feed before being linked to the city water system, and the Lighthouse’s close proximity to other amenities such as schools for their children.

In 1925, Martha unexpectedly died, and approximately two months later, Austin died from what was termed as a “broken heart.” However, the Austin legacy at Pt. Fermin continued when their 24 year old daughter, Thelma, applied for and was granted the position of lightkeeper.

In a 1920’s circa article in Women’s World magazine, Thelma was asked about why said had assumed her parent’s role as the lightkeeper at Pt. Fermin. Thelma thoughtfully responded, “Almost everyone asks me that question. If you would have associated with lighthouses and the sea as much as I have, you would know that I never could get lonesome so long as the pounding of the breakers is audible, and the ocean liners continue to sail my door. And instead of growing monotonous and tiresome, the regular routine about the lighthouse seems a great source of comfort to me.”

Fireplaces were the primary heating source for the Lighthouse. In the 1970’s restoration efforts were begun. Later restoration efforts included earthquake retrofitting of the building including its three chimneys.

It was not long after that that the light was electrified in 1924. With electrical power the flashing beam of light extended 18 miles beyond the shoreline. Automation also reduced the need to maintain a full-time lightkeeper. Thelma’s duties at Pt. Fermin were reduced along with her salary. To supplement her income, she worked in a dentist’s office in the City of Wilmington.

Eventually Austin left the Lighthouse and the property fell under the care of the City of Los Angeles. The City of Los Angeles continued to oversee the property while the light was maintained by the U.S. Coast Guard. The City continued in its role as caretaker until the beginning of World War II.

The Lighthouse provided picturesque views of the Catalina Channel and served as an excellent coastal lookout station during World War II.

With the attack on Pearl Harbor life along the Pacific Coast and Pt. Fermin changed. Coastal regions were placed under black out orders and Pt. Fermin’s light was extinguished. The U.S. Navy assumed possession of the property and converted Pt. Fermin into a radar station and coastal lookout station. This once proud sentinel of the sea was stripped of its light and lens. The circular lantern room at the top of the Lighthouse was converted to a square structure housing a coastal lookout station.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Lighthouse was placed under the control of the U.S. War Department and converted into a coastal lookout station. The Lighthouse remained in this configuration until the early 1970’s.

Following the war, the Lighthouse’s beam was replaced by a coastal beacon mounted on a pole, similar to those used at airports, on the cliffside below the lighthouse. The Pt. Fermin Lighthouse and surrounding property was once again placed under the care of the City of Los Angeles and became the residence for the park maintenance supervisor.

In the early 1970’s the U.S. Coast Guard’s plans to demolish this local landmark were stopped by a local resident with a strong sense of the building history. Since his early childhood, Bill Olesen developed a fondness for the Lighthouse and could not bear the thought of the building falling victim to the wrecking ball. Olesen quickly recruited San Pedro’s own living legend and Coordinator of the Cabrillo Marine Museum, John Olguin, to lead a campaign to save the beloved landmark. Through their efforts, in June 1972, they were able to have the Lighthouse included on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Lighthouse stabilized its water supply issues by incorporating a gravity water system that allowed them to incorporate indoor plumbing. The development of the City of San Pedro expanded and the Lighthouse was incorporated into their municipal water system.

Taking their campaign one step further, they found the original blueprints for the building and began restoration projects that included the building’s exterior and interior. One of the major projects was dismantling the lookout station and returning it to the original lantern room configuration.

Returned to its original state, the Lighthouse is a stunning presence along the Peninsula’s coastline.

To complete the restoration process, Olesen and Olguin set out to find the lens that was removed from the Lighthouse at the start of World War II. The pair were in a restaurant discussing their situation when they met a individual who provided them with a tip that led them to a real estate office in the City of Malibu owned by Louis Busch.

When they met Busch, he was skeptical about the pair’s story and indicated that the lens was on exhibit at a nautical museum on the Santa Monica Pier that was created by a former lifeguard captain, “Cap” George Watkins. When the pier was damaged, Watkins brought the lens to his home where it remained until his death. According to Busch, following Watkins death, his son presented the lens to Busch.

After her appointment as Curator of the Pt. Fermin Lighthouse, Kristen Heather took an active role in resolving this situation and determining the authenticity of the lens that was found in Busch’s office. The Federal Real Property Agency placed Joanna Nevesny, a member of the Coast Guard Auxiliary, and Jim Woodward, a Fresnel lens expert, in charge with determining the legitimacy of the claims. Nevesny and Woodward determined that if the screw holes on the lens hinge could be examined on the lens Busch had acquired with the screw holes shown in photographs of the hinge on the lens that was originally housed at Pt. Fermin, it would allow them to determine if the lens in Busch’s office was the same lens originally mounted in the lantern room at Pt. Fermin.

This is the last lens that was in place at the Lighthouse prior to the beginning of World War II. The lens was removed during the war and placed in a nautical museum in the City of Santa Monica. Before its return to the Lighthouse, the lens was displayed in a real estate office in Malibu.

Woodward explained that each lens was produced by hand and no two lenses have the same screw hole pattern on the mounting plate. Carefully comparing the actual plate with one in the photographs could provide a definite answer to the question. After careful examination, Nevesny and Woodward determined that the lens in Busch’s office did come from Pt. Fermin.

Busch could not argue with the proof and agreed to return the lens to the lighthouse. On November 13, 2006, the lens was retrieved from Busch’s office by Woodward along with members of the Pt. Fermin Lighthouse Society (PFLS).

On December 16, 2006, a homecoming ceremony was held at the lighthouse celebrating the return of the lens. Then Los Angeles City Councilwoman, Janice Hahn, presented a congratulatory plaque to the PFLS and the public was invited to see the lens proudly displayed on the first floor of the Lighthouse.

Through the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000, in 2012 the Lighthouse was made available to federal, state, and local agencies, non-profit corporations, educational agencies, and community development organizations for purposes including: educational, recreational, cultural, or historic preservation. Although 53 Expressions of Interest were received, only four groups submitted applications by the November 9, 2012, deadline. On January 20, 2015, the Lighthouse, adjacent guest quarters and coastal lookout were awarded to the City of Los Angeles with the assistance of the PFLS and the Pt. Fermin Historical Society. The properties were formally transferred in December 2018.

Prior to and since being awarded, the Lighthouse and adjacent properties the City of Los Angeles, the Port of Los Angeles, the State of California and the PFLS have conducted extensive restoration, retrofitting, and renovation projects of the Lighthouse and property.

As the City of Los Angeles and PFLS celebrate the 150th anniversary of the maritime and historical landmark, a number of events will be conducted throughout the year. Highlighted events include Lighthouse Heritage Day, Fleet Week/Veterans Exhibits, Tea by the Sea, Beer and Wine Tastings, Lighthouse Photo Contest, 150th Festival of Lights, and Los Angeles Lighthouse Challenge. The Lighthouse Challenge takes place on July 13, 2024, and will incorporate a celebration of all three lighthouses found on the Peninsula: Pt. Fermin Lighthouse, Angels’ Gate Lighthouse, and Pt. Vincente Lighthouse.

The City of Los Angeles Parks and Recreation Department and the Pt. Fermin Lighthouse Society continue to preserve and present information on the Lighthouse’s historical past.

Sponsorship opportunities are available to assist with defraying the cost of the events as well as supporting the PFLS and its various projects needed to maintain this historic landmark.

The lighthouse is open to the public Tuesday through Sunday from 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. and admission is free, but donations are requested. It is closed on Mondays and major holidays. Guided tours are offered at 1:00 p.m., 2:00 p.m., and 3:00 p.m. Reservations are not necessary for the general public, but for large groups or private tours contact the PFLS in advance of your visit.

The Lighthouse is located at 807 W. Paseo Del Mar in San Pedro. For more information contact (310) 241-0684 or visit www.laparks.org/pflighthouse. The PFLS website can be found at www.pflhs.org.

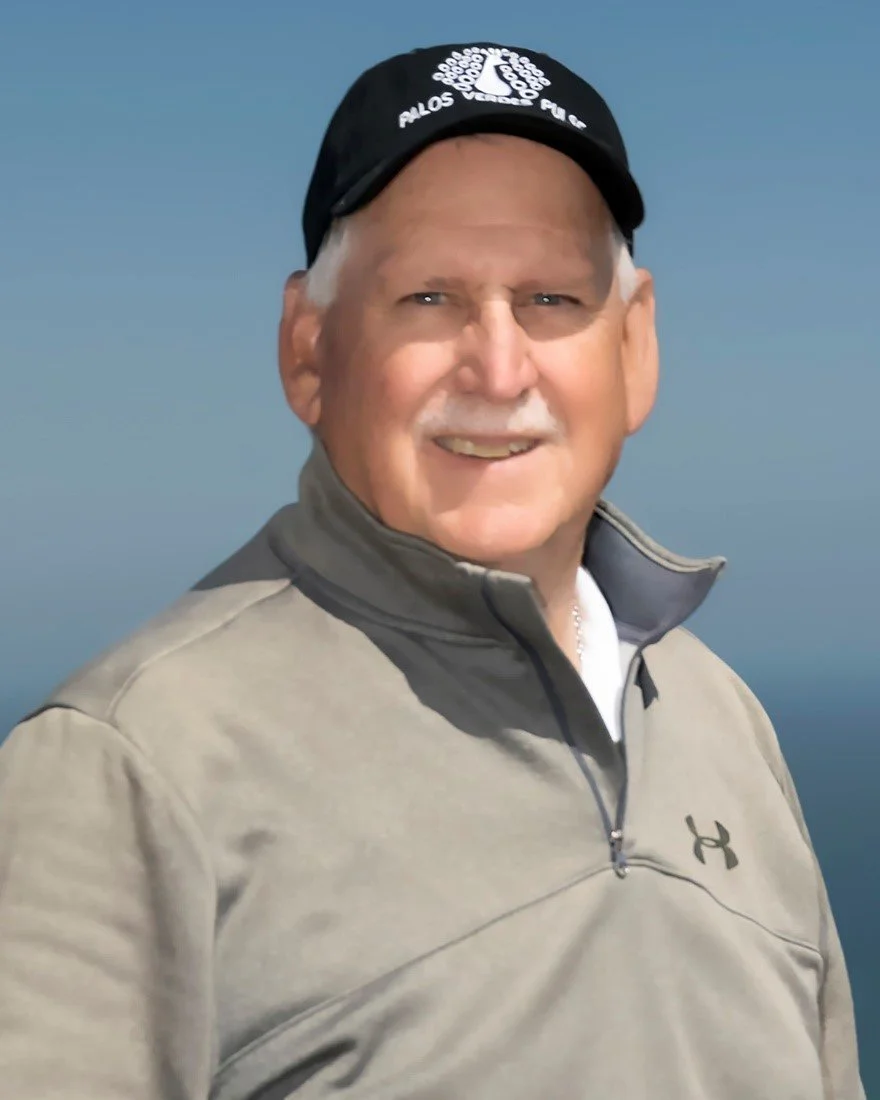

Steve Tabor

This South Bay native’s photographic journey began after receiving his first 35 mm film camera upon earning his Bachelor of Arts degree. As a classroom teacher he used photography to share the world and his experiences with his students. Steve began his photography career photographing coastal landscapes and marine life. His experiences have led him to include portraits and group photography, special event photography as well as live performance and athletics in his portfolio. As a contributor and photojournalist, he has published stories about the people, places and events in and around the Palos Verdes Peninsula and beyond.

Interested in seeing more of Steve’s work, visit website at: www.stevetaborimages.com